|

Illustrating Empire A Visual History of British Imperialism

Ashley Jackson & David Tomkins

Oxford: The Bodleian Library, 2011 Paperback. 216 pp. £19.99. ISBN 978 185124 3341

Reviewed by Adam Stephenson Université de Picardie Jules-Verne, Amiens

With its 1.5

million different items—advertisements, playbills, postcards, labels,

programmes, menus, games, ballads, match boxes, posters and so on dating from

the 16th to the 20th centuries—the John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera

at the Bodleian Library in Oxford is one of the largest of its kind in the

world. And with the ‘pictorial turn’ in the humanities, the vogue for history

‘from the bottom up’, the current interest in new kinds of historical sources,

the post-modern distrust of grand historical narratives and the well-attested

shorter attention spans of today’s readers, it might be thought that its hour

had come. This is

certainly what the curators think. They are in the process of digitising 65,000

items and putting them on the Internet so that researchers, students, schools

and amateurs can have access to them, and they project a whole series of

history books based on the collection. Illustrating Empire: A Visual History

of British Imperialism is the first of these. The authors,

Ashley Jackson, Professor of Imperial and Military History at King’s College

London and David Tomkins, Project Manager at the collection, have arranged

their material under eight chapter headings covering the main aspects of the

British imperial experience insofar as they feature in the collection:

emigration and settlement, imperial authority, exploration and knowledge, trade

and marketing, travel and communications, leisure and popular culture, jubilees

and exhibitions, and politics. In apparently well-informed, sensible and entertaining

prose, they have written an introduction to each chapter, a paragraph or two of

comment on each of the two hundred or so items and a general introduction to

the volume. If we see it

as an attractive, instructive and relatively inexpensive coffee-table book of

Victoriana and related matter, the work can be considered a success. Readers

will enjoy the sunny picture of the Empire which emerges from this delightfully

varied selection—advertisements for Canadian emigration and Australian dried

fruit; commemorative images of heroic expeditions and royal visits; vivid

depictions of native life (doc.1); celebrations in exhibitions, songs,

shows and board games—tempered by a few denunciatory (if, alas, mostly

image-free) pamphlets and posters (doc.2). However, when we try to

consider Illustrating Empire on its

own terms, as the flagship not only of a new series of historical works, but of

the John Johnson Collection or even of new sciences of ephemerology and visual

history, then our judgment must be more nuanced. To put it schematically, the

authors do a bad job of writing, thinking and looking, and in the process,

often make their images less visible. I will treat each of these points in

turn.

(1) One of a series of four pictures of Australian life (1853) This

sloppiness is due in part to a general policy of informality: right margins are

not justified, the layout is user-seductive, the tone positively matey. Out of

a ‘kaleidoscope of images’ in a ‘gallimaufry of forms’, say the authors, they

have chosen a ‘medley…drawn at random’ from the collection. Not as randomly as

all that, thank goodness, but to get at the truth about these images and the

history they emerge from, the reader has constantly to negotiate linguistic

obstacles. The authors’ taste for the vocabulary of amusing and edifying

generality constantly misleads us: Imperium et libertas, they say, was ‘a popular phrase …

bandied about by, among others, Winston Churchill’; no it wasn’t, it was the

motto of the Primrose League, founded by Winston’s father, Lord Randolph; ‘a

Royal Proclamation of

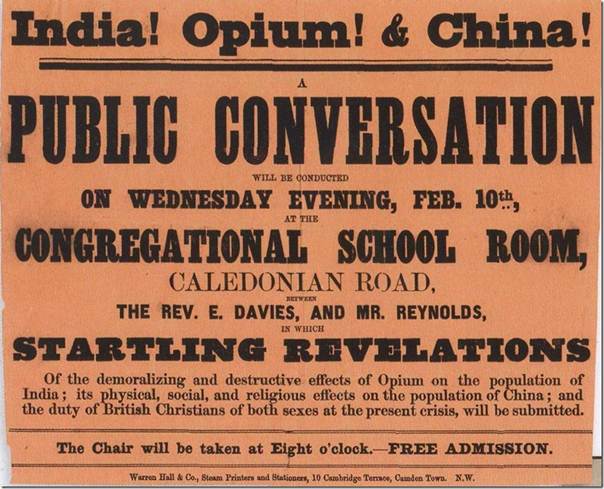

(2) Poster advertising a meeting with a missionary who had been in China, mid-19th century However, the

authors’ carelessness with words sometimes seems to derive from a deeper

confusion or ignorance. Basic historical concepts are used clumsily, not only

abstractions like representation (the verb ‘to purvey’ is a particular

favourite) and causality (‘to create’, etc.), but also supposedly more

empirical notions (‘the Westminster political structure’, ‘the political

media’, ‘politicized’, ‘exploitation’). Occasionally, they stray into the

territory of postcolonial studies (‘to appropriate’, ‘the Western gaze’,

‘knowledge and power’, etc.), but without any apparent awareness of what this

vocabulary brings with it, apart, apparently, from a right to condescend to the

past. Their use of sneer quotes is a good example of this. Inverted commas are

splashed around so liberally to mean ‘so-called’ (“superiority”, “improve”,

“civilizing”, “experts”, “discovery”, “native law and custom” and so on) that

we no longer know when they correspond to genuine quotations: evangelicals and

utilitarians, we are told, saw the Empire as leading towards ‘human

“upliftment”’; no they didn’t, the word was unknown in the 19th

century. Sometimes, the authors trip

themselves up on their quotes: ‘Some of the “barbaric”

practices that (the missionaries) sought to eradicate', they say, are still

considered “barbaric” ’; no: they are still considered barbaric. Quotation marks are abused throughout the work, now put around indirect speech, now omitted from passages lifted directly from the Internet.

And when they are replaced by the more candid ‘so-called’, this misfires, too:

the authors talk about ‘the so-called Communists in Southeast Asia’, as if the

Communist Party of Malaya and the MNLA were either figments of the British

imagination or a bunch of impostors. Condescension

also appears in non sequiturs. ‘Some (locals) were duly impressed, some

indifferent, some contemptuous of British pretensions and the inequity (sic)

of rule by foreign intruders. Nevertheless, the British enjoyed considerable

success in co-opting indigenous elites.’ This ‘nevertheless’ is wrong, for the

contradiction it announces is not with the apparently balanced previous

sentence, but with the unspoken assumption that of course British rule

was iniquitous and contemptible. (The word ‘duly’ in the cliché ‘duly

impressed’ is one for the gullible natives.) ‘Exploration exoticized the wider

world,’ we are told, but this can hardly be true, for the baroque monsters

peopling maps and imaginations prior to exploration were infinitely more exotic

than anything that came after, and anyway, elsewhere the authors say, a little

more plausibly, that explorers and anthropologists ‘revealed how people lived’. Sometimes they go beyond condescension and

simply denounce their wicked subjects: ‘Joseph Chamberlain, the most egregious

imperial politician’, etc. Most perverse is their moralistic denunciation of

what they take to be 19th-century moralism: one missionary paper, they say (doc. 3), ‘strikes a typical moralizing tone’ in condemning Maori images; no it

doesn’t, it calls the images ‘uncouth’, which is aesthetic, not moral

condemnation, and it explains this by saying that the artists ‘change the glory

of the uncorruptible God into an image made like to corruptible man,’ which is a

theological reason, not a moral one. The words are familiar from Romans 1:23; standing behind them

are the Second Commandment and the story of the Golden Calf, and they served

against Catholics more than Maoris. Unfortunately, this is not the only

quotation the authors miss, to the impoverishment of their commentary. The word

‘typical’ here (‘typical moralizing tone’) and elsewhere tells us as much about

their own bland stereotypes as about the documents themselves. Certainly the

largely positive images the book offers us need to be placed in a more nuanced

context, but not in such ways as these. Occasionally the authors redress the

balance, saying kind things about the missionaries’ educational role and

denunciation of abuses, or comparing imperial publicity with today’s ‘fair

trade’ pictures of ‘happy “native” women picking tea’, but the moral they draw—that

we are no better than our forebears—should make them more cautious about

condescending to their own typecast version of the past.

(3) CMS Missionary Papers, 1816 More serious

than any problem of attitude is the authors’ technical incompetence. They

mishandle basic historical tools such as statistics, now needlessly precise,

wrongly transcribed and taken from a single year but supposed to show growth

over decades, now rounded out and fitted into punchy-sounding but meaningless

sentences like ‘as late as the 1960s tens of thousands of children from British

orphanages and care homes were sent to Australia and other settler colonies’.

Tens of thousands … per year? we ask. Per decade? Between the beginning of the

century and 1967, perhaps, but we can’t be sure. Even when the facts and figures

are accurate and unambiguous, they too often serve to dazzle rather than

enlighten. Even worse, in

a book of images, is the treatment of the images themselves. The authors nearly

always use them as a pretext to talk about something else. Sometimes, by a

process we might call ‘vertical conflation’, they run together different levels

of reality, not distinguishing the book’s illustrations from the exhibition

programmes, matchboxes, board games, etc. they represent, nor these from the

pictures on them, and these latter hardly ever from the scenes, people, things

and places depicted. At other times, by a process we might call ‘horizontal

conflation’, they sidestep to whatever takes their fancy, as when an engraved

portrait of George Augustus Selwyn, the first Bishop of New Zealand—or rather,

a photo of an unidentified page containing it—is flanked by a paragraph devoted

in large part to someone else, James Brooke, the White Rajah of Sarawak, or

when, despite a tempting scene from Treasure

Island, what must be the cover of a 1930 travel brochure for a

cruise inspires a comment which mentions neither the cover nor the brochure nor

the cruise, but tells us instead in pointless detail how, when and where the

cruise ship met its end: ‘Of 832 passengers and crew, all but 5 survived’ (sic, doc. 4). Elsewhere, images of

magazine covers give rise to gossip about the magazines themselves, their

founders, fates, etc. This is certainly not the stuff of the ‘visual history’

we were promised in the title.

(4) Cover of a travel brochure (partly obscured by a

related but unexplained item), 1930, and caption A special case

of this ‘horizontal conflation’ is the slippage from a particular imperial

image to social representations of the Empire that we see whenever the authors

touch on the question of ‘the extent to which British society was, or was not,

affected by imperial ideas.’ This has been an object of particularly lively

debate recently, both because of its intrinsic historical interest and because

of what it tells us about who we are supposed to blame for the British Empire.

Although they announce that they are ‘seeking not to take sides’ in the debate,

the authors go on to tell us dozens of times not only that ‘British society’

was ‘saturated’, ‘steeped’, ‘suffused’, ‘permeated’, etc. with imperial

imagery, references and so on but also that these ‘shaped’ (or occasionally,

‘helped shape’) ‘British perceptions’. But how can we be sure of this? A

collection showing only imperial imagery can tell us nothing about the much

greater mass of non-imperial imagery; and we would need to know who saw these

images, in what circumstances, how their behaviour changed afterwards, etc. In

November

(5) Stanley in Africa, the kind of aggressive, exciting, amoral image proposed by Dean Several of

their pictures, for example, come from two publications, Dean’s Gold Medal Series, n°14, Stanley in Africa (doc. 5) and Darton’s Heroes in Africa (docs. 6 & 7: both

dated ‘c.1890s' (sic)—in fact 1890). They are included in the chapter on

Exploration and Knowledge, alongside missionary reports, the ground plan of

Rhodes House, etc. and are treated similarly, the first being described as a

‘magazine…which presented stereotypical images of Africa’, the second as a

‘brochure’ whose ‘stories present common, albeit false, assumptions about

Africa’. But this is all grossly misleading. These are not ‘magazines’ or

‘brochures’—perhaps for adults—but toy books, a familiar Victorian genre, not

really ephemera at all and, more importantly, not for adults but for children,

something which Jackson and Tomkins contrive not to notice. It is as if we had

not distinguished The Beano and

The Uses of Literacy. Most of the numbers in Dean’s series—Struwelpeter of Today, Stories about Jesus, Some Old Nursery Friends, etc—say

nothing about Africa or the Empire, any more than do most of Darton’s

publications. Dean had his books translated into other tongues including

Swedish, not the language of a noticeably imperial nation in the 1890s (pace

Norway), and Darton’s ‘common, albeit false’ assumption ‘that only European

action could end the evils of the slave trade’ seems to me not false, but

demonstrably true (not that European action did entirely wipe out the slave

trade). And the description of the slave caravan given by Darton (doc.6) is, as far as I am able to

ascertain, accurate enough for a children’s book.

(6) The more edifying vision of Africa proposed by Darton More

importantly, the authors do not seem to notice that these two works and the

images they contain are very different; indeed, in an article in BBC History Magazine July 2011

(accessible on the Internet) they confuse the two, giving the clearly printed

cover of Dean’s Stanley in Africa the

caption ‘Darton’s Heroes in Africa’. But the two rival children’s publishers

see the world very differently. The enterprising Dean is cashing in on the

short-lived Stanley craze (he brought out spinoffs including a sort of jigsaw

puzzle of his brutal, amoral pictures); Darton, on the other hand, the

successor to a long line of Quaker publishers, tries to fill the young reader

with pity for the victims of the slave trade. With a little attention, the

different character of the images leaps to our eyes. Both include a shooting

scene (docs. 5 & 7), but Darton

does not show crazed savages being slaughtered, only arrows which have all

fallen wide; the hero and his men are not arrayed in an immovable straight line

stretching to infinity, but crouched defensively behind trees; etc. Jackson and

Tomkins see no further than the catch-all ‘stereotypes’ and ‘common

assumptions’ that they themselves have brought to the pictures. (Not that such

stereotypes are absent; but more needs to be said.)

(7) Darton’s hero in a tight spot Too often, the

authors not only do not see the image they have in front of them, but they make

it difficult for us to see it too. An engraving of East India House in 1803 is

accompanied by an account of an earlier building on the site. ‘Above the Doric

pilasters,’ say the authors, describing Ionic columns, ‘was a frieze of

treglyphs (sic), symbolizing the prudence and wisdom of the Company.’ Triglyphs

cannot symbolise anything much—perhaps metopes are meant—and in such an abysm

of ignorance, we cannot expect any competent speculation on, say, the different

reasons why such dull classicism was preferred to the Neo-Mughal style chosen

by returning Company nabobs at Daylesford, Sezincote and elsewhere. Worse, we are

not told the size of any of the objects represented, and many of them have been

reduced, making the pictures difficult to appreciate and the words illegible (a

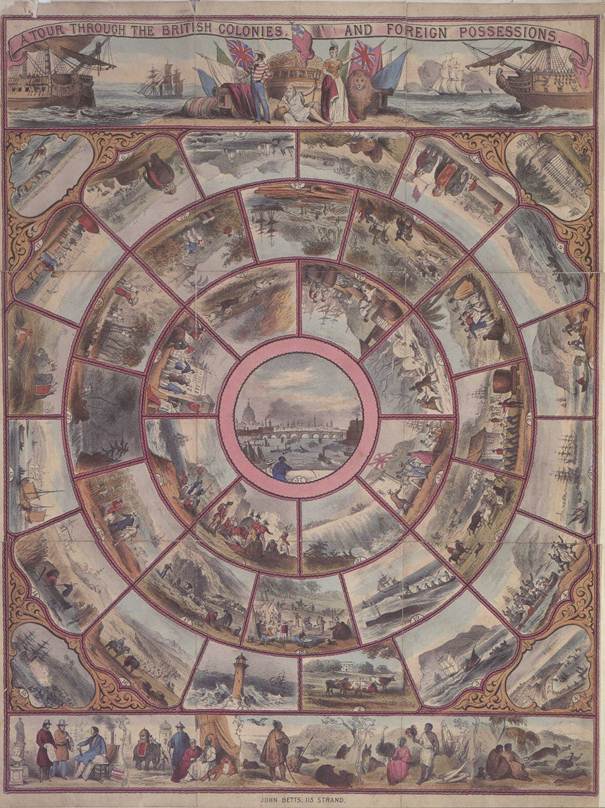

problem also on the Internet site of the collection). A splendid-looking board

game from

(8) A Tour Through the British Colonies and Foreign Possessions, John Betts &

Co, 1855

Even worse, we

are hardly ever told the nature of the pictures, and never that some of them

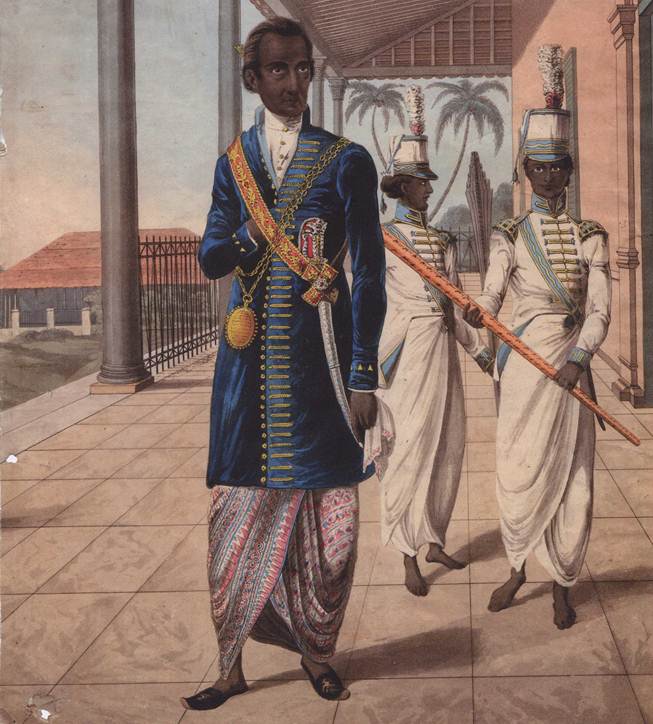

have been cut to fit onto one page. Among these is one of my favourites, A Nobleman in Ceylon (late eighteenth

century) (doc.10). Where does it come from? What is its size

and medium? Whose is the title? Even: does it belong in a collection of

ephemera? The authors describe the image as ‘emphasizing the status of

indigenous elites within the imperial system’; but ‘status’ is hopelessly vague

(high status?/low status?), the ‘emphasizing’ belongs to the historian, not the

source, and the ‘imperial system’ in question is not British but Dutch, for, as

they go on to say, ‘in the late 18th century....Ceylon was ruled by the Dutch’.

(This is not quite accurate, either, for they have forgotten the independent

Kingdom of Kandy.) And once again the authors wade out of their depth into

unfamiliar vocabulary, saying nonsensically that ‘(the nobleman’s) dhoti, with

kastane with lion-headed hilt, is almost certainly… produced on the Coromandel

coast.’ One would like to have been told more about the striking mixture of

Eastern and Western clothes, the significance of the right hand tucked into the

coat, etc. ‘Expertly

written,’ says a back-cover testimonial from a serious historian who should

have known better, and ‘beautifully reproduced’—perhaps the image on his front

cover is less like a botched Photoshop job than the ill-cut, dark, discoloured

one on mine. I will not discuss minor mistakes which a halfway competent

proof-reader would have picked up—part of the introduction to Chapter 6

included in Chapter 7, documents and what they represent misidentified, etc.—but

quickly conclude with the reflection that the title, Illustrating Empire: A Visual History of British Imperialism, is a triple misnomer: firstly, one cannot

illustrate ‘Empire’, but only a text with pictures or an argument or theory

with examples; secondly, this is not a history of British Imperialism, for too

much is missing and too much non-imperial material is included; and thirdly, it

does not correspond to any defensible notion of visual history, except,

minimally, to the history of what things looked like. Furthermore, as a plea

for printed ephemera, it is very misleading, given that the most historically

instructive ephemera—trade lists, classified advertisements, etc.—are often

textual not iconographic. In short, apart from the undeniable charm and

interest of many of the images it contains, this work belongs with the ephemera

it promotes, and may be of as much concern to historians of libraries,

publishing and careers in the 21st century as to students of the British Empire

in the 18th, 19th and 20th.

(10) A Nobleman

in Ceylon (late 18th century)

Cercles © 2012

|

|

|

|